From cod to clingfilm, the advice we’re given can often be confusing. If you’re serious about eating green, here are some straightforward solutions.

Is almond milk really the nuts?

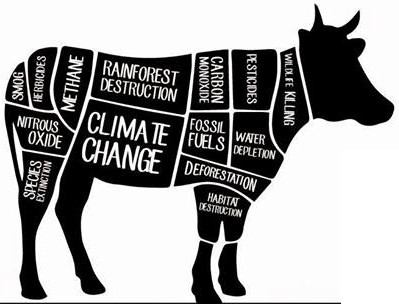

Influenced by clean eating and agri-exposés such as Cowspiracy (whichpointed to methane emissions from cattle as crucial in global warming), many are ditching cows’ milk in favour of non-dairy alternatives, which, according to Euromonitor, now make-up 12% of global milk sales.

That sounds positive. Pre-shipping, the carbon created by a litre of semi-skimmed (1.67kg) is far higher than that of almond milk (360g). “But what people don’t know is the environmental damage almond plantations are doing in California, and the water cost. It takes a bonkers 1,611 US gallons (6,098 litres) to produce 1 litre of almond milk,” says the Sustainable Restaurant Association’s Pete Hemingway.

Over 80% of the world’s almonds are grown in California, which has been in severe drought for most of this decade. Hemingway describes a situation in which farmers are ripping up relatively biodiverse citrus groves to feed rocketing demand for almonds, creating a monoculture fed by increasingly deep water wells that threaten statewide subsidence issues. That leaves rather a bad taste in the mouth.

Solution: of the dairy alternatives, oat milk is the most sustainable option, according to Hemingway.

Thank cod! The fish we can eat again

When campaigning organisations hit the panic button, the message – in this case: cod is endangered, don’t eat it – can stick, long after it is relevant. Fish stocks are dynamic, points out the Marine Stewardship Council’s George Clark. Advice changesand responsible consumers need to stay abreast of that: “There’s a lot of confusion about cod, but there are plentiful supplies of MSC-certified cod in the north-east Atlantic. About 91% of Norway’s catch is certified.”

Solution: get (certified) cod back on your menu.

Bioplastic is not fantastic

Many street food vendors have switched to bioplastic – which sounds like an ethical choice. But, while it may make street food feel virtuous, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace challenge its green rep. It is resource intensive and less than 40% of bioplastic is designed to be biodegradable. In many ways, it is just another polluting plastic.

Solution: want to eat green on the go? Carry cutlery in your bag.

Cling to your clingfilm

Post-Blue Planet II, professional kitchens are all #chefsagainstplastic. London’s Spring restaurant, for instance, was using 3,600km of clingfilm a year. Now it uses beeswax wrapping. But harassed home cooks need to take a more nuanced view. Within reason (wrapping half a lime is daft), not wasting food should be your environmental priority. “Clingfilm can play an important role in that,” says Hemingway.

Solution: buy more Tupperware.

Put equality at the heart of ecology

The rush to ban plastic straws and the resulting outcry from disability campaigners(who, for various medical and practical reasons need plastic straws), crystallised how the social impact of green initiatives needs greater consideration. The next battleground, predicts Sue Bott, deputy chief executive of Disability Rights UK, will be food and drink venues banning bottled water and replacing it with water fountains: “Reducing plastic use is laudable, but our lives become more restrictive if changes are introduced overnight.”

Solution: let consumers choose.

Don’t bottle it

According to Crystal Market Research, the US reusable water bottle market will be worth $9.62bn by 2023, up $3bn in a decade. A recent Keep Britain Tidy/Brita survey found that 55% of us own a refillable bottle, but only 36% of us carry it regularly. Ideally, buy one made from recycled materials (eg Eco-Bottles), and use it.

Solution: keys, phone, purse/wallet, water bottle – make it part of your daily routine

Local ≠ sustainable

With fish, terms such as “local”, “day-boat” and “line-caught” are now seen by many consumers as a guarantee of sustainability. They are not, says Clark, who points to overfishing of sea bass as an example of what happens when fishing is not rigorously scrutinised by a third party, such as MSC: “Sustainability has to encompass fish stocks, their management and environmental impact.”

Solution: stick to fish objectively certified as sustainable

Take a clear view on plastic bottles

Manufacturers can label any bottle that can feasibly be recycled as recyclable. In reality, says Friends of the Earth’s Emma Priestland, weirdly designed or coloured bottles are likely to be sifted out at recycling sites and will end up in landfill: “Robinson’s Fruit Shoot bottles are made of easily recycled Pet, but because [one version] is solid purple, it’s difficult to recycle. If separated, opaque colours can be recycled by chemical recycling, but that increases the cost, effort and energy required,” she says. The European Pet Bottle Platform, which advises the bottling industry on design, recommends the use of clear Pet if possible.

“All of our Pet plastic packaging, including Fruit Shoot, is fully recyclable in the UK recycling system,” says Robinson’s parent company, Britvic, a founding signatory of the new UK Plastics Pact. It adds: “We moved to a more translucent [Fruit Shoot] bottle in February.”

Solution: keep your use of outlandishly designed bottles to a minimum.

The breakdown on compostable packaging

Naively, you might think that the compostable-plastic takeaway tub you ate your lunch from is easily compostable and that, if you dropped it into a food waste bin, in a few months some keen gardener will be scattering it on their allotment. That is highly unlikely. These plant-based, PLA-plastic products need to be industrially composted in specific units that are so scarce in Britain, most compostable packaging is burned or goes to landfill.

In fact, put that compostable salad tub in a food waste bin and you actually create a problem. Food waste is composted by anaerobic digestion to produce biogas and fertiliser, but, first, any packaging has to be removed. “Compostable products have no gas value,” says a spokesperson for waste recycler ReFood. “Drivers check customers’ bins when they collect. If there is a lot of packaging, then they won’t be able to accept the waste, but this doesn’t happen very often.”

In its initial production, compostable packaging is more eco-friendly than traditional plastic packaging, but, at the moment, it is no silver bullet.

Solution: at lunch, rather than a takeaway from the works canteen or a local cafe, sit in and eat off a plate using metal cutlery. It is far greener. “Until the waste infrastructure is in place, telling people packaging is 100% compostable is, at best, problematic and, at worst, greenwash,” says the Carbon Trust’s Jamie Plotnek.

Switch to sustainable tofu

In South America, soy farming (mostly for animal feed), is driving deforestation and the destruction of Brazil’s Cerrado grasslands. “Both release huge amounts of carbon dioxide and are a biodiversity disaster,” says Dr John Kazer, footprint certification manager at the Carbon Trust. Usually 90% less, tofu originating from deforested Brazilian pastures has a carbon footprint twice that of chicken.

Solution: choose tofu brands (eg Taifun) that source super low-carbon European or US soy.

One bottled water you can drink guilt-free

Sales of bottled One Water were down 30,000 in the first half of this year at the University of Manchester. Fantastic, you may think. But One Water is no ordinary bottled water: the company is carbon neutral and its profits fund clean-water projects in the developing world (£17.4m so far). As for the plastic waste, there is a robust market in recycled Pet bottles. Where those bottles are segregated in bins from glass, paper and other waste, as they are at the university, you can be confident they will be recycled.

Solution: do your due diligence before swerving a product. “We fully support One Water,” says Alexander Clark, an environmental coordinator at the university. One Water founder Duncan Goose saysyear-on-year growth continues but admits: “Concern over single-use plastics is having an impact on our industry.”

Sometimes the easy option is the right one

Cooking in industrial food manufacturing is more efficient than cooking at home, which makes using pre-cooked rice or tinned chickpeas over dried an energy saver. (Don’t worry about the can: there is healthy demand for recycled steel.) Think about using a microwave, too, advises Kazer: “For smaller portions for one or two, compared to the hob, the energy use is a lot lower.”

Solution: think about (packaging issues notwithstanding) how processed, preserved and pre-cooked food can help you reduce your food waste and energy use.

A bag really is for life

In terms of combatting immediate environmental pollution, the 5p plastic bag charge has been a huge success. Britain now uses 6.5bn fewer bags annually. But a Danish government study worries some experts. “There’s a fear people are not reusing heavier bags enough,” says Hemingway, “to the extent the volume of bag-plastic in circulation could actually be increasing.” As we all accumulate bags, could this be creating an eco-anomaly?

Solution: you need to use your bag-for-life eight times before its carbon footprint is lower than an ordinary carrier bag. An organic cotton tote must be used 149 times to be in credit. Keep them handy. Use them often.

Eat New Zealand lamb

Imported New Zealand lamb has a lower carbon footprint than British lamb, concluded a 2009 report for Defra. Kiwi lamb is reared at such a low intensity that, even after shipping, it uses less energy. Of course, there are other issues around sustainability that mean you may still want to support British sheep farmers, but that starkly illustrates how “food miles” are no measure of a product’s green credentials, and that there are no easy answers to global warming.

Solution: if you want to regularly slam in the lamb, look down under.

• This article was amended on 5 September 2018. An earlier version quoted Pete Hemingway as saying to make 1 litre of almond milk, it takes 1,611 litres of water. Hemingway was referring to a study that found it takes 1,611 US gallons, not litres, of water. This has been corrected.

This article was published first in theguardian.com.